Stoning In Iran: A Deep Dive Into A Controversial Punishment

Table of Contents:

- The Roots of Stoning in Iran's Legal System

- A Historical Overview of Stoning's Implementation

- The Moratorium and Its Limitations

- Why the Moratorium Failed to Halt the Practice

- The Horrific Nature of Stoning: A Detailed Look

- Adultery and Capital Punishment: The Primary Offence

- The Burden of Proof: Confession, Witness, or Judge's Conviction

- Documented Cases and Unofficial Numbers

- International Outcry and Diplomatic Pressure

- High-Profile Cases and Their Global Impact

- Defending the Practice: Internal Perspectives

- The Ongoing Struggle for Abolition

The Roots of Stoning in Iran's Legal System

To comprehend the persistence of stoning in Iran, one must first understand its legal foundation. Iran's penal code explicitly includes stoning as a possible form of punishment. This legal framework allows for penalties to be based on *fiqh*, which refers to traditional Islamic jurisprudence. Within this traditional interpretation, provisions for stoning are indeed found. It's crucial to note that capital punishment is a legal penalty in Iran for a range of crimes, including murder, plotting to overthrow the Islamic government, and, notably, adultery. While stoning has been around for centuries as a historical practice in various cultures, its formal re-establishment as a legal punishment in Iran is relatively recent. Death by stoning came into force in Iran after the 1979 revolution, which transformed the country's legal system to align more closely with Islamic law. However, it wasn't until 1983 that stoning officially became a legal form of punishment in the codified law. Before this formal codification, stonings were not consistently documented, making their previous rate of occurrence largely unknown. This formalization in 1983 marked a significant shift, embedding the practice firmly within the nation's legal structure, and setting the stage for its continued, albeit controversial, application. The very inclusion of stoning within the penal code, even with subsequent attempts to curb it, signifies a deep-seated adherence to certain interpretations of religious law.A Historical Overview of Stoning's Implementation

The journey of stoning from a traditional concept to a codified law in Iran reveals a complex interplay of religious interpretation, political will, and societal norms. While the 1979 revolution laid the ideological groundwork for a return to Islamic law, the specifics of its implementation, including the reintroduction of stoning, evolved over the subsequent years. The 1983 codification was a pivotal moment, cementing its place in the legal system. Since then, Iran has unfortunately gained the grim distinction of having the world's highest rate of execution by stoning, a practice that regularly draws international headlines due to its extreme nature. This historical trajectory underscores that stoning is not merely an ancient custom but a contemporary legal reality, periodically enforced by the Iranian judiciary.The Moratorium and Its Limitations

In 2002, a significant development occurred when the head of Iran’s judiciary issued a moratorium on stoning sentences. This move was widely seen as a response to mounting international pressure and a recognition of the severe criticism the practice garnered globally. However, the impact of this moratorium proved to be limited. It was more of a guideline or an instruction to judges rather than a fundamental change to the law itself. This distinction is crucial: because the penal code still contained stoning as a possible form of punishment, judges retained the discretion to impose such sentences. Consequently, despite the official moratorium, various instances of stonings in Iran have been documented since 2002. This highlights a persistent challenge in Iran's legal system, where judicial interpretations and guidelines can sometimes diverge from the letter of the law, and where official directives may not always translate into consistent practice across all courts. The continued occurrence of stonings post-moratorium indicates that the underlying legal provisions remain active, allowing for the practice to persist, albeit perhaps less frequently or with more attempts at discretion.Why the Moratorium Failed to Halt the Practice

The effectiveness of the 2002 moratorium was undermined by its very nature: it was an administrative directive, not a legislative amendment. This meant that the legal basis for stoning remained intact within the penal code. Judges, drawing upon *fiqh* and the existing law, could still technically issue stoning sentences, even if discouraged by the judiciary's head. Furthermore, internal pressures and differing interpretations of Islamic law among judicial figures may have contributed to the continued, albeit unofficial, application of the punishment. The fact that a judicial panel reportedly reinserted a stoning provision into a draft law, as noted by Human Rights Watch, further illustrates the ongoing internal struggle and the fragility of any attempts to fully abolish the practice of stoning in Iran. This complex legal landscape makes the fight against stoning a continuous uphill battle for human rights advocates.The Horrific Nature of Stoning: A Detailed Look

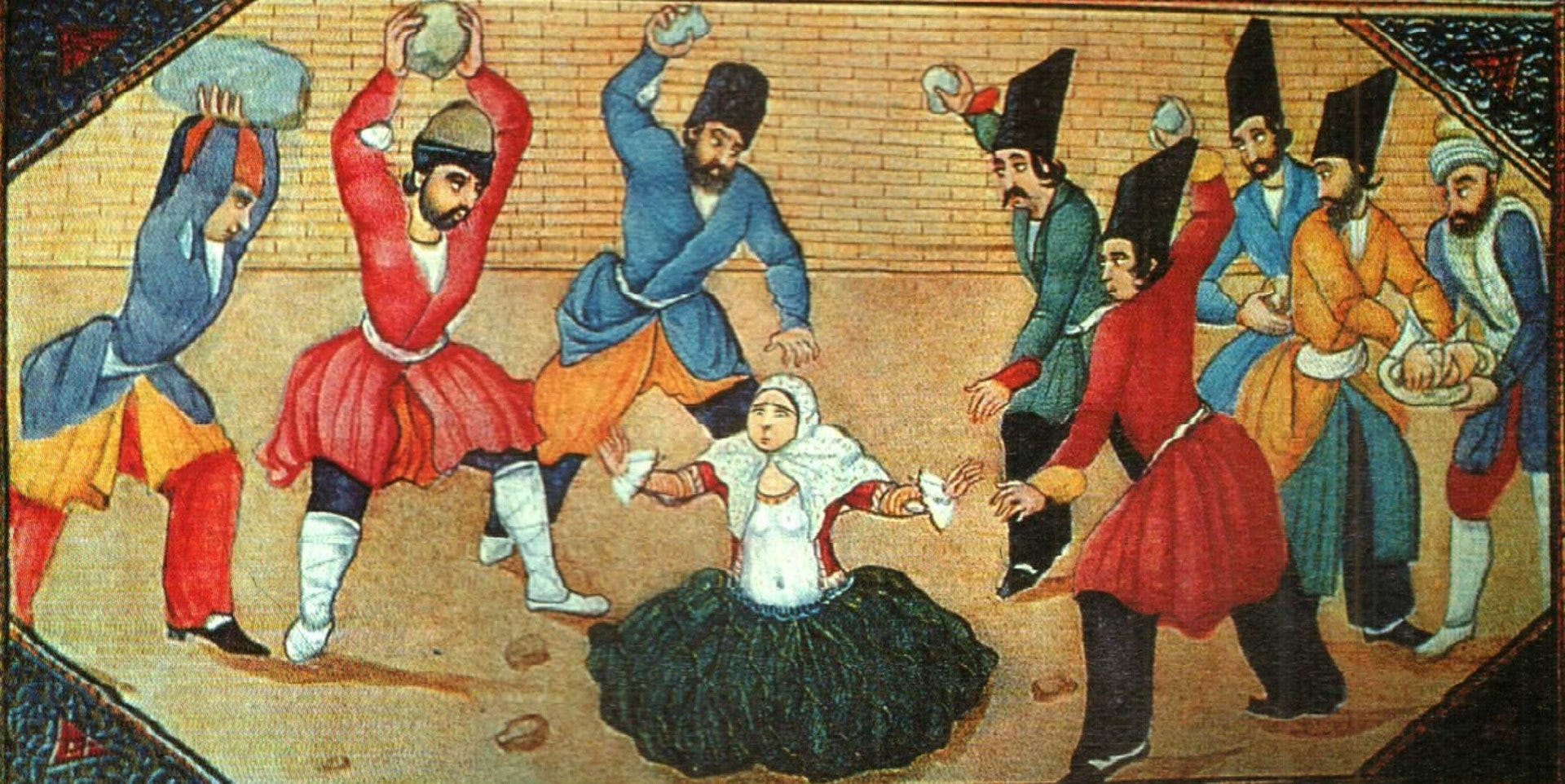

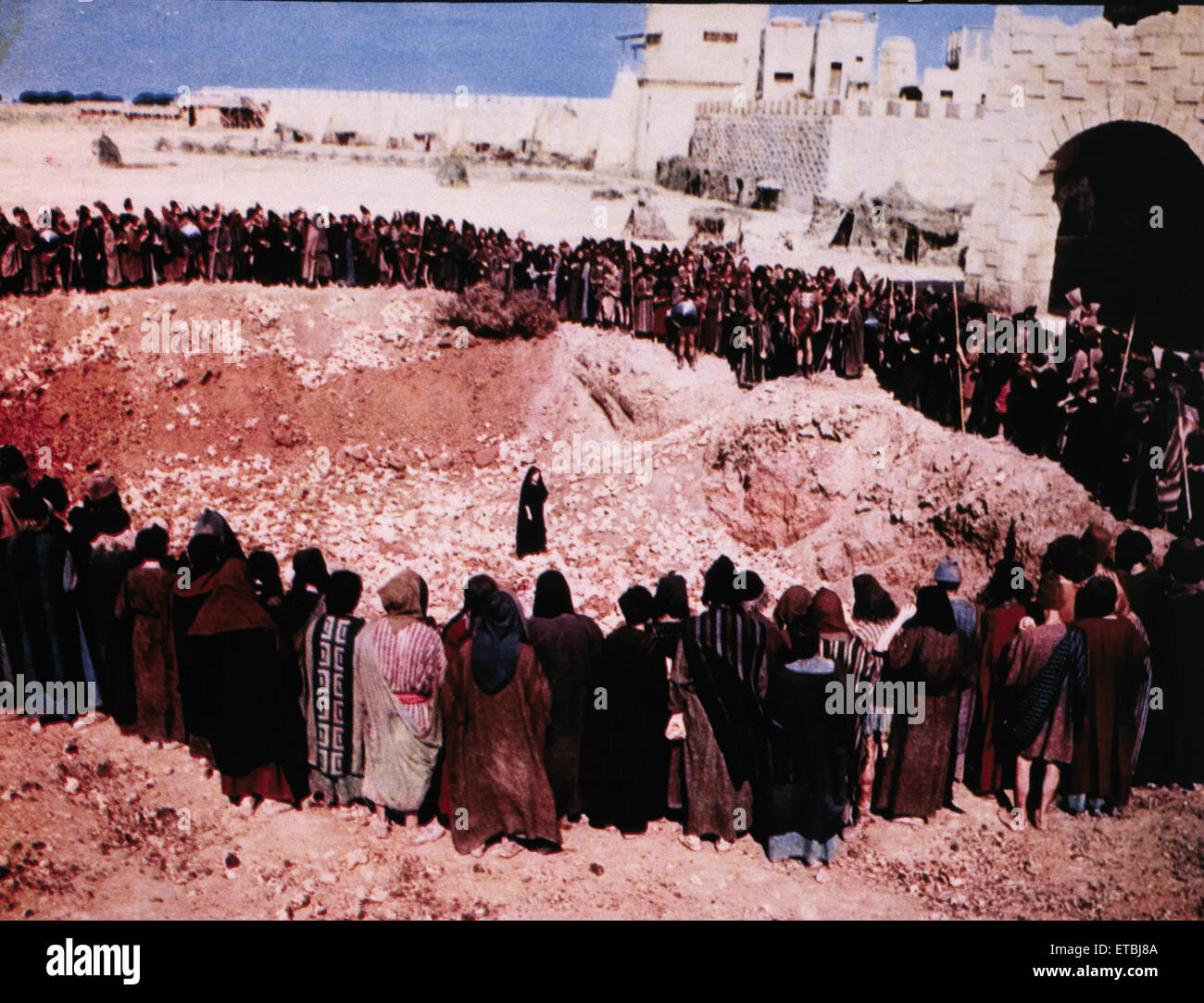

Execution by stoning, as prescribed in Iran’s penal code, is widely recognized as a particularly grotesque and horrific practice. Its method is designed not for immediate death but for prolonged suffering. The law itself dictates specific parameters to ensure this prolonged agony: the stones used must be large enough to cause pain, but crucially, not so large as to kill the victim immediately. This chilling detail underscores the deliberate intent behind the punishment – to inflict maximum suffering before death. Article 102 of the penal code further specifies the burial positions for those sentenced to stoning. Men are to be buried up to their waists, while women are buried up to their breasts. This ensures that the condemned individual is largely immobilized, unable to defend themselves or escape the barrage of stones. Amnesty International, a leading human rights organization, vehemently opposes the death penalty in all circumstances and believes that stoning is specifically designed to increase the suffering of victims, making it an especially cruel, inhuman, and degrading form of punishment. The physical and psychological torment inherent in this method makes it an extreme violation of human dignity, drawing universal condemnation from human rights bodies worldwide.Adultery and Capital Punishment: The Primary Offence

While capital punishment in Iran applies to a range of serious crimes, including murder and acts against the state, Iranian courts sometimes sentence people to death by stoning primarily for adultery. This particular offense, when committed by married individuals, carries the potential for this extreme penalty. The legal framework surrounding adultery and its punishment is complex. Interestingly, stoning sentences for adultery can sometimes be reduced to lighter punishments upon appeal. This possibility of reduction upon appeal suggests a degree of judicial flexibility or perhaps a response to public or international pressure in certain cases. The severity of the punishment for adultery reflects a strict interpretation of moral and religious codes within Iran's legal system, emphasizing what are perceived as "family values." However, the application of such a brutal punishment for a non-violent offense like adultery remains a major point of contention and a primary focus of international human rights advocacy against stoning in Iran.The Burden of Proof: Confession, Witness, or Judge's Conviction

Iranian law spells out three primary ways an alleged adulterer can be sentenced to stoning, each carrying its own set of evidentiary requirements. The first is through the defendant's confession. If an individual confesses to adultery, this can be sufficient grounds for a conviction leading to stoning. The second method involves witnesses testifying to the defendant’s guilt. This typically requires a specific number of credible witnesses to the act itself. The third pathway is when the judge convicts the defendant based on their own assessment of the evidence presented, even without a confession or direct witness testimony, though this is often based on circumstantial evidence or a judge's interpretation of *fiqh*. These methods of proof highlight the judicial process that can lead to such a severe sentence, underscoring the importance of fair trial standards and due process, which human rights organizations often argue are lacking in these cases.Documented Cases and Unofficial Numbers

Despite the clandestine nature surrounding many stoning cases, efforts by human rights organizations have brought some statistics to light. Iran has the world’s highest rate of execution by stoning, yet no one knows with certainty how many people have been stoned in Iran. The exact number remains elusive due to the lack of official transparency and the varied reporting mechanisms. However, according to a list compiled by the human rights commission of the National Council of the Iranian Resistance, at least 150 people have been stoned in Iran since 1980. Further data indicates that between 1983, when stoning became a legal practice and its documentation began, and 2014, there were approximately 150 documented cases of stoning in Iran. This figure, while significant, likely represents only a fraction of the actual occurrences, as many cases may go unreported or unconfirmed. The discrepancy between the 1980 and 1983 starting points for documentation further complicates the precise count, but both figures point to a consistent, albeit horrifying, application of this punishment over decades. The very difficulty in obtaining accurate numbers underscores the secretive and often arbitrary nature of these executions, making it challenging for international bodies to monitor and intervene effectively.International Outcry and Diplomatic Pressure

Iran has consistently faced intense international pressure for its extensive use of the death penalty, and particularly for its employment of stoning. The grotesque nature of stoning often triggers a swift and powerful global outcry, which sometimes leads to tangible results. When Iranian officials have faced substantial public outcry over a stoning sentence, they have, on occasion, backed down or freed accused individuals. A notable example is the case of Makarrameh Ebrahimi in 2007, where international pressure reportedly played a role in her eventual release after being accused of adultery and facing stoning. Another significant case involved Hoda Jabari, aged 24, who was suspected of adultery in Iran and faced stoning to death. However, the European Court intervened, preventing Turkish authorities from returning her to Iran to face the possible stoning. Hoda was subsequently allowed to stay in Turkey and eventually leave to seek a new life in Canada. These instances demonstrate the power of international advocacy and the critical role played by human rights organizations and foreign governments in preventing these executions. The pressure is not always successful, but it often puts the Iranian judiciary in a difficult position, forcing them to consider the diplomatic repercussions of their actions.High-Profile Cases and Their Global Impact

Beyond Makarrameh Ebrahimi and Hoda Jabari, the case of Sakineh Mohammadi Ashtiani (born 1967) garnered immense international notoriety. She was an Iranian woman convicted of conspiracy to commit murder and adultery, originally sentenced to death by stoning for her crimes. Her case became a rallying cry for human rights activists worldwide, with governments, celebrities, and ordinary citizens joining the chorus of condemnation. The intense global spotlight on her situation put significant pressure on the Iranian government, demonstrating how individual cases can ignite a powerful international movement. While the specifics of her final outcome are complex and debated, the international outcry undeniably played a pivotal role in preventing her stoning and drawing unprecedented attention to the practice of stoning in Iran. These high-profile cases serve as stark reminders of the human cost of this punishment and the vital importance of continued international vigilance and advocacy.Defending the Practice: Internal Perspectives

Despite the widespread international condemnation, some Iranian officials and conservative figures have publicly defended stoning. Javad Larijani, an Iranian conservative politician and former diplomat, is one such figure. He has defended stoning for adultery, asserting that it is a "good Islamic law" that protects "family values." This perspective reflects a deeply rooted belief among certain segments of Iranian society and the ruling establishment that stoning is a legitimate and necessary component of Islamic justice, designed to uphold moral order and social stability. The argument often centers on the idea that these punishments deter moral transgressions and preserve the sanctity of the family unit, which is considered a cornerstone of Islamic society. This internal defense highlights the ideological divide between those who view stoning as a barbaric human rights violation and those who see it as a divinely sanctioned punishment essential for maintaining societal integrity. Understanding this internal rationale is crucial for comprehending why the practice persists despite external pressure, as it underscores a fundamental difference in legal and moral interpretations.The Ongoing Struggle for Abolition

The fight against stoning in Iran is a continuous and arduous struggle. While the 2002 moratorium offered a glimmer of hope, its limitations quickly became apparent, with the practice continuing under the radar. Human rights organizations, such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, remain vigilant, consistently documenting cases and advocating for the complete abolition of stoning. These groups regularly report on individuals who still face the threat of stoning, with Human Rights Watch stating that Iranian authorities are holding at least 10 people who currently face this grim fate. The fact that a judicial panel has reportedly reinserted a stoning provision into a draft law indicates the fragility of any progress made and the constant threat of the practice being more firmly entrenched. The international community, led by various human rights bodies, continues to pressure Iran to end this "particularly grotesque and horrific practice." The goal is not merely to impose another moratorium but to achieve a permanent legislative change that removes stoning from Iran's penal code entirely. Until then, the risk of stoning remains a stark reality for many in Iran, making the ongoing advocacy for its abolition more critical than ever. In conclusion, the issue of stoning in Iran is a complex tapestry woven from legal precedent, religious interpretation, and intense international human rights advocacy. From its post-revolution re-codification to the often-ineffective moratoriums and the persistent efforts of global organizations, the practice remains a deeply troubling aspect of Iran's justice system. The documented cases, though likely underreported, paint a grim picture of a punishment designed for prolonged suffering, primarily applied for adultery. The international outcry, though not always immediately successful, has demonstrably led to reprieves in high-profile cases, underscoring the power of global solidarity. However, the internal defense of stoning by some Iranian officials, who view it as a necessary tool for upholding "family values," reveals the profound ideological chasm that must be bridged for true abolition. The ongoing struggle by human rights groups to remove stoning from Iran's penal code entirely is a testament to the enduring commitment to human dignity and the universal opposition to such a cruel and inhuman punishment. We invite you to share your thoughts on this critical human rights issue in the comments below. What do you believe is the most effective way to address the practice of stoning in Iran? Your perspective contributes to a vital global conversation. For more in-depth analyses of human rights issues and international law, explore other articles on our site.

What Happens in a Typical Stoning? | by Carlyn Beccia | Jun, 2021 | An

Stoning death hi-res stock photography and images - Alamy

Spanish Artist Seeks To Bring Attention To The Dreadful Practice Of