Iran's Clergy: Unpacking Power, Influence, And Evolution

Table of Contents

- The Deep Roots of Clericalism in Iran

- The Clergy's Enduring Social Fabric

- Power Dynamics: Clergy, State, and the Supreme Leader

- The 1979 Revolution: A Clerical Ascent

- Shifting Sands: Declining Clerical Influence?

- Jurisdictional Reach: The Clergy's Legal Authority

- The Future of Clerical Power in Iran

- Conclusion: Navigating the Complexities of Iran's Clergy

The Deep Roots of Clericalism in Iran

The history of the clergy in Iran is as ancient and intricate as the nation itself. For centuries, the Shia ulema, or religious scholars, have served not merely as spiritual guides but also as community leaders, educators, and, at critical junctures, as political arbiters. This deep historical embedding means that Islamic clericalism in Iran has had a remarkable and pervasive impact on Iranian society, politics, and Islamic theology. Unlike some other Islamic traditions, the Shia clergy developed a hierarchical structure and a system of independent funding, which allowed them to maintain a degree of autonomy from the state. This autonomy often positioned them as a counterbalance to secular rulers, giving them significant moral authority and a direct line to the populace. Throughout various dynasties, from the Safavids who established Shia Islam as the state religion in the 16th century, to the Qajars and the Pahlavis, the clergy consistently played a pivotal role. They were instrumental in preserving Iranian identity and culture, often acting as custodians of traditional values against foreign influences. Their mosques, seminaries, and religious endowments (waqfs) formed a parallel infrastructure that often rivaled state institutions in reach and influence. This long-standing historical presence has ensured that even in modern Iran, understanding the dynamics of the clergy is essential to grasping the country's political and social landscape. Their legacy is etched into the very foundations of the Islamic Republic, a testament to their enduring historical power and the profound influence they wielded over generations of Iranians.The Clergy's Enduring Social Fabric

One of the most striking aspects of the clergy in Iran is their unparalleled social reach. Unlike many political or economic elites, clerics form the broadest social network in Iran, exerting their influence from the most remote village to the biggest cities. This extensive network is built on centuries of trust, religious education, and community engagement. Through local mosques, husseiniyehs (religious meeting halls), and charitable foundations, clerics are often the first point of contact for many Iranians seeking guidance, resolving disputes, or accessing social services. They are deeply embedded in the daily lives of ordinary citizens, attending funerals, weddings, and religious ceremonies, which reinforces their social legitimacy and influence. This pervasive presence means that even if their political power is debated or perceived to be shifting, their social influence remains a formidable force. They are not merely figures of authority but also familiar faces, often seen as guardians of morality and tradition. This grassroots connection allows them to disseminate ideas, mobilize support, and gauge public sentiment in ways that few other institutions can. Their sermons, lectures, and personal interactions shape public opinion and maintain a cultural continuity that transcends political shifts. This deep social embedding is a critical factor in understanding why the clergy, despite facing various challenges, continue to be an indispensable part of Iran's social and cultural landscape.Ulema: The Learned Men of Islam

Central to the concept of the clergy in Iran is the term "ulema." Collectively, they are called the ulema, meaning learned men or Islamic scholars. This term encompasses a wide range of religious figures, from local prayer leaders and seminary students to grand ayatollahs who are considered sources of emulation (marja' taqlid). The ulema undergo rigorous training in seminaries (hawzas), studying Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh), theology (kalam), philosophy, ethics, and Quranic exegesis. This extensive education grants them the authority to interpret Islamic law and guide their followers on matters of faith and practice. The ulema are not a monolithic entity; they represent diverse schools of thought, political leanings, and interpretations of Islamic law. While united by their shared religious learning, they often engage in robust debates on theological, social, and political issues. This internal dynamism, though sometimes hidden from public view, is a vital aspect of their intellectual tradition. The authority of the ulema is derived not from state appointment but from their scholarly achievements and the recognition of their followers. This independent source of legitimacy has historically allowed them to challenge state power and advocate for the rights of the people, making them a unique and powerful force in Iranian society.Power Dynamics: Clergy, State, and the Supreme Leader

Understanding the intricate power dynamics within Iran requires a nuanced view of the relationship between the elected government and the clerical establishment. While Iran’s current president, Masoud Pezeshkian, took office in July 2024, his power, like that of his predecessors, is limited by design. The president primarily manages economic and domestic policy, overseeing the ministries and bureaucracy. This executive function, while crucial for the day-to-day running of the country, operates within a framework ultimately controlled by a higher authority. The core of power in the Islamic Republic rests with the Supreme Leader, a position that must be held by a Shia jurist. As the most powerful figure in Iran, the Supreme Leader holds ultimate and unchecked authority, overseeing all major state affairs, including foreign policy, military, and judicial matters. Among analysts of Iranian affairs, there is little disagreement that the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and the clerical establishment are Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei's most significant instruments of power. The IRGC, a powerful military and economic force, acts as the protector of the revolution's ideals, while the broader clerical establishment provides the ideological backbone and social legitimacy for the system. This structure leads to a complex answer to the question: are the clerics losing their power in Iran? It is not realistic to consider the clerics as being the ruling class of Iran in the conventional sense, as power is concentrated in the Supreme Leader and his allied institutions. At the same time, one cannot ignore that the Supreme Leader, by definition, is a Shia jurist, meaning that the highest office is intrinsically linked to the clergy. While the president handles daily governance, the strategic direction and ultimate decisions flow from the clerical leadership, demonstrating a unique integration of religious authority and state power that defines the Islamic Republic.The 1979 Revolution: A Clerical Ascent

The 1979 revolution stands as a watershed moment in Iranian history, fundamentally altering the nation's political landscape and cementing the central role of the clergy in Iran. This revolution, which brought together Iranians across many different social groups, has its roots in Iran’s long history of popular movements and intellectual ferment. The aim of this essay is to examine how and why the clergy and the religious societies of Iran, comprising the religious opposition, overthrew the Pahlavi dynasty. The revolution was not a singular event but consisted of two main phases: the initial broad-based opposition to the Shah's autocratic rule, which included secular nationalists, leftists, and various religious groups, and the eventual consolidation of power by the clerical leadership under Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. The clergy, with their extensive social network and moral authority, were uniquely positioned to mobilize the masses. They provided a coherent ideology rooted in Islamic principles that resonated with a populace disillusioned by the Shah's Westernization policies, corruption, and authoritarianism. Historical analyses, such as those found in "The Modern Revolutions of Iran, Civil Society and State in the Modernization Process" and "A Chronographic Analysis of the Constitutional Revolution of Iran," highlight the recurring pattern of clerical involvement in major political upheavals, including the Constitutional Revolution of 1905-1911. The clergy's organizational capacity, their ability to communicate through mosques and religious networks, and their perceived independence from the Shah's regime made them the most effective force in leading the opposition. While most opposition groups participated in the 1979 revolution, it was the clerical leadership that ultimately seized the reins of power, establishing the Islamic Republic. This historical context is crucial for understanding the enduring power and influence of the clergy in Iran today, as their current position is a direct outcome of their pivotal role in overthrowing a monarchy that had ruled for centuries. This wasn't the first time religious figures had influenced political outcomes, as seen in the days leading up to the August 19, 1953, overthrow of Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddeq, where religious figures played a role in the political climate.Shifting Sands: Declining Clerical Influence?

Despite their historical dominance and entrenched position, there are growing indications that the influence and popularity of the clergy in Iran may be experiencing a significant shift. An important indication of this decline is the proportion of clerics in Iran’s parliament (Majlis). While the exact numbers for the current (10th) Majlis are not provided in the data, the implication is that their representation is not as dominant as one might expect given their historical power. This suggests a potential disconnect between the clerical establishment and the broader political representation. The diminishing popularity of the clergy in Iran appears to stem from a confluence of factors, primarily worsening economic conditions and escalating corruption concerns. For many ordinary Iranians, the promise of the revolution has not translated into improved livelihoods. High inflation, unemployment, and a perceived mismanagement of the economy have led to widespread discontent. This economic hardship directly impacts the public's perception of the ruling establishment, including the clergy, who are seen as responsible for the nation's governance.Economic Woes and Public Discontent

Economic struggles are a major driver of public dissatisfaction with the clergy in Iran. Merchants, a traditionally supportive base for the clerical class, have faced diminishing gains from trade as foreign currency subsidies for importing essential goods were reduced or eliminated entirely. This has led to higher prices, reduced purchasing power, and a general sense of economic precarity for many. When the economic well-being of the populace declines, so too does their trust in those in power, including the clerical establishment. Moreover, widespread allegations of corruption, often involving powerful figures and institutions, further erode public confidence. The perception that resources are being siphoned off or mismanaged while ordinary citizens struggle fuels resentment and leads to questions about the moral authority of the clergy. This growing disillusionment is a significant challenge to the legitimacy of the clerical system, as their historical legitimacy was often tied to their perceived piety and commitment to justice.Voices of Dissent Within the Clergy

The challenges facing the clergy in Iran are not limited to external public discontent; there is also significant internal unrest. In a climate where many clerics are unhappy about their situation and some are losing faith in the Islamic Republic, the purported minutes of a recent regime meeting show how the problem may evolve as domestic unrest continues. This internal dissent suggests that the clerical establishment is not a monolithic entity, and even within its ranks, there are profound disagreements and anxieties about the future. These contentious debates, however, are not limited to a select few, but include a number of the most notable clerics in Iran. These influential figures, often revered for their scholarship, might voice concerns about the direction of the country, the erosion of revolutionary ideals, or the perceived disconnect between the ruling establishment and the people. Such internal critiques, when they emerge, can be particularly damaging to the system's legitimacy, as they come from within the very group that is supposed to uphold its principles. This indicates a deeper crisis of confidence that could have significant implications for the long-term stability and influence of the clergy in Iran.Jurisdictional Reach: The Clergy's Legal Authority

The influence of the clergy in Iran extends deeply into the legal system, showcasing their pervasive authority beyond mere political governance. The Supreme Court Council (SCC), a powerful judicial body, exemplifies how clerical authority can assert itself even in seemingly secular legal matters. An example of the SCC spreading its jurisdiction is a case involving a press offense which the SCC took on the grounds that “the defendant is a member of the clergy.” This particular case, involving ‘Ali Afsahi, chief editor of the cultural and sports magazine Sinama va Varzesh, on December 30, 1999, is notable because Afsahi was explicitly *not* a cleric. Despite this, he was imprisoned for four months, with the SCC seemingly using the pretext of his alleged clerical status to assert its jurisdiction. This incident highlights a critical aspect of the clerical establishment's power: its ability to define and expand its legal reach, sometimes even bending conventional legal interpretations. It underscores how the judiciary, deeply intertwined with the clerical system, can be used to enforce ideological conformity or suppress dissent, even when the direct connection to the clergy is tenuous. The power to interpret and apply Islamic law (Sharia) grants the clergy immense authority over all aspects of public and private life, from personal status laws to criminal justice. This jurisprudential foundation is what underpins the unique legal system of the Islamic Republic, where religious principles are paramount. This study reviews the critical junctures in the history of political Shiism and its theories to shed light on the jurisprudential and philosophical foundations that allow such interpretations and extensions of clerical authority.The Future of Clerical Power in Iran

The future of the clergy in Iran is a subject of intense debate and speculation, particularly in light of ongoing social and political transformations. Iran’s protests, which intensified around December 2022, have brought with them increasingly vocal calls for Shia clerics to step back from politics. This sentiment reflects a growing segment of the population, especially among younger generations, who desire a more secular or at least less overtly clerical form of governance. The historical study of political Shiism and its theories provides a crucial lens through which to understand these contemporary challenges, illuminating the jurisprudential and philosophical foundations that have historically shaped the clergy's role and how they might evolve. The calls for the clergy to retreat from direct political involvement are not merely a rejection of specific policies but often a fundamental questioning of the concept of *velayat-e faqih* (guardianship of the jurist), the foundational principle of the Islamic Republic that grants ultimate authority to the Supreme Leader. As domestic unrest continues, the problem of clerical legitimacy and public acceptance may evolve in unpredictable ways, potentially leading to significant shifts in the balance of power.The Constitution and Democratic Claims

A central point of contention regarding the legitimacy of the clerical system lies in the very foundation of the Islamic Republic. Leaders of the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) dismiss critics of the country’s political system by claiming that the constitution, which grants ultimate and unchecked authority to an unelected religious leader, was born of democratic process. This claim refers to the referendum held shortly after the revolution, which approved the new constitution. However, critics argue that a single referendum, conducted in a revolutionary atmosphere, does not negate the inherent contradiction of a system that vests supreme power in an unelected cleric, effectively limiting the scope of popular sovereignty. This debate over the democratic legitimacy of the system is fundamental to understanding the ongoing tensions between the ruling establishment and segments of the Iranian population. The clerical leadership faces the challenge of reconciling its religious authority with the modern demands for democratic accountability and transparency, a task that becomes increasingly difficult amidst economic hardship and widespread calls for reform.Conclusion: Navigating the Complexities of Iran's Clergy

The role of the clergy in Iran is a multifaceted and evolving phenomenon, deeply rooted in history yet constantly adapting to contemporary challenges. From their profound historical impact on Iranian society, politics, and theology to their enduring social network that reaches every corner of the nation, the clergy remain an indispensable force. However, their power is not monolithic; while the Supreme Leader, a Shia jurist, holds ultimate authority, the president's role is more limited, and the clerical establishment itself is a complex web of varying opinions and influences, including the formidable Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. The 1979 revolution undeniably elevated the clergy to a position of unparalleled political power, yet recent years have seen a perceptible shift in their public standing. Diminishing popularity, fueled by economic woes, corruption concerns, and even internal dissent among some clerics, suggests a period of significant re-evaluation. Calls for the clergy to step back from politics are growing louder, reflecting a societal desire for change. The unique legal authority wielded by the clerical establishment, as demonstrated by the Supreme Court Council's jurisdictional reach, underscores their pervasive influence across all state functions. As Iran navigates its future, the trajectory of the clergy in Iran – their power, their influence, and their relationship with the populace – will undoubtedly remain a central determinant of the nation's path. What are your thoughts on the evolving role of the clergy in Iran? Do you believe their influence will continue to wane, or will they adapt to maintain their central position? Share your perspectives in the comments below, and explore more articles on our site for deeper insights into Iranian society and politics.

264 best Clergy images on Pholder | Ghostbc, Exmormon and Eu4

The Clergy

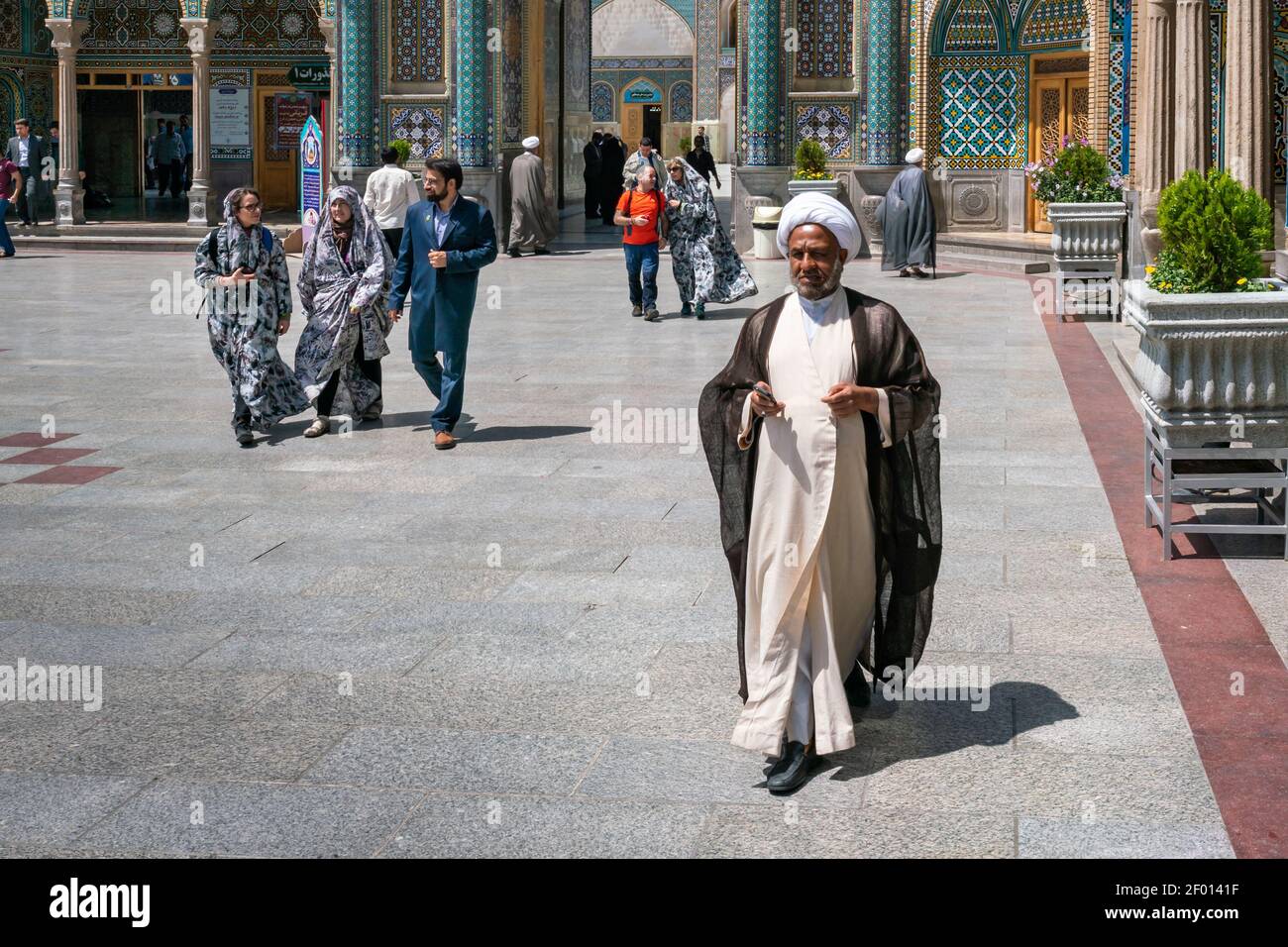

Qom, Iran - 04.20.2019: Islamic clergy in traditional dress walking in