Unveiling Iran's Constitutional Revolution: A Pivotal Chapter

The Genesis of Discontent

For centuries, Iran had been a monarchy, with power concentrated in the hands of the Shah. However, by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, this traditional system faced increasing pressure. Economic woes, foreign interference, and the perceived weakness and corruption of the Qajar dynasty fueled widespread discontent among various segments of society, including merchants, ulema (clergy), intellectuals, and even some members of the aristocracy. The desire for reform, justice, and a more accountable government began to coalesce, setting the stage for the constitutional movement in Iran. This movement was not a sudden eruption but a gradual build-up of grievances and aspirations, driven by a growing awareness of modern political thought and the success of similar movements elsewhere.The Spark of Revolution

The period from early 1323 AH (corresponding to 1905 CE) to the convening of the first Majlis in October 1906 was characterized by intense revolutionary ferment. This was a time when competing groups vied for leadership, each with their own vision for Iran's future. From the earliest gatherings and public protests to the circulation of clandestine tracts, the demand for change grew louder and more insistent. These early manifestations of dissent were crucial in mobilizing public opinion and pressuring the Qajar monarchy. The movement in opposition to the Shah's rule gained momentum, ultimately leading to the momentous decision to convene the Majlis, a parliament that would, for the first time, limit the absolute power of the monarch and introduce a form of representative government.Ideological Currents Shaping the Movement

The Iranian Constitutional Revolution was not monolithic in its ideology; rather, it was a complex tapestry woven from various intellectual and religious threads. Scholars recognize four distinct phases of an ideological process during the revolution itself. These phases reflect the evolving understanding of constitutionalism, the role of religion, and the nature of the state among the diverse groups participating in the movement. From calls for a just Islamic government to more secular demands for parliamentary democracy and civil liberties, the ideological landscape was rich and often contradictory. This intellectual ferment was crucial in shaping the debates and outcomes of the revolution, highlighting the tension between traditional values and modern aspirations that defined the constitutional movement in Iran. The movement's literature, including newspapers, pamphlets, and books, played a vital role in disseminating these ideas and mobilizing public support.The Convening of the Majlis and Royal Resistance

The persistent pressure from the constitutional movement ultimately forced the Shah, Mozaffar al-Din Shah Qajar, to issue a decree for the establishment of a parliament in August 1906. This was a monumental victory, leading to the convening of the first Majlis in October 1906. The new assembly immediately began drafting a constitution and a set of electoral laws, aiming to establish a constitutional monarchy. However, the path to a truly constitutional government was far from smooth. Mozaffar al-Din Shah died shortly after the Majlis convened, and his successor, Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar, was deeply autocratic and hostile to the constitutional principles. He viewed the Majlis as an infringement on his divine right to rule and harbored a strong desire to restore absolute monarchy. This royal resistance would soon plunge the nation into further turmoil.The Shah's Backlash and the Dark Days of 1908

Mohammad Ali Shah's disdain for the constitutional movement in Iran reached its peak in 1908. Two days before a pivotal event, the Shah extended an invitation to the leaders of the constitutional movement to the imperial gardens outside Tehran. This seemingly conciliatory gesture was, in fact, a trap. There, he imprisoned all save for one who miraculously managed to escape, signaling his clear intent to crush the nascent democratic aspirations. The most infamous act of repression occurred on June 24, 1908, when the Shah placed the Majlis under siege and ordered its bombardment by artillery fire. This brutal act destroyed the parliament building, dispersed its members, and effectively ended the first constitutional period, ushering in a period of royalist reaction known as the "Minor Tyranny." This violent suppression underscored the deep divisions within Iranian society and the immense challenges faced by those advocating for constitutional rule.Key Players and Complex Dynamics

The constitutional movement was a broad coalition, but it was also characterized by internal struggles and shifting alliances. Understanding the various groups and their roles is crucial to grasping the complexity of this pivotal period in Iranian history.The Rise of Political Parties

The constitutional period saw the emergence of various political parties, albeit in a nascent and often fluid form. These groups, ranging from liberal constitutionalists to more radical social democrats and traditionalist clerics, played a crucial role in shaping public discourse and mobilizing support. They published newspapers, organized meetings, and debated the future of Iran, reflecting the diverse aspirations within the movement. While not always cohesive, these parties represented a significant step towards modern political organization in Iran, laying the groundwork for future political developments. Their debates and struggles highlighted the challenges of forging a unified vision for a constitutional state in a society undergoing rapid transformation.The Baha'is and Their Complex Relationship

The Baha'is, a religious minority in Iran, had a particularly complex relationship with the constitutionalist movement. An excerpt from a book on the history of Iran includes mention of Baha'i schools in the early twentieth century, indicating their presence and engagement in modernizing efforts. While some Baha'is supported the constitutional movement, their involvement was often viewed with suspicion by certain factions, particularly those with strong clerical ties. The Baha'i historian of the constitutional movement, Haj Aqa Muhammad ‘Alaqihband, noted that the Azali involvement in the Constitutional Revolution was duplicitous. According to ‘Alaqihband, their real aim was to completely overthrow the Qajar monarchy and place Azal himself on the throne of Iran. Evidence for ‘Alaqihband's assertion comes from the Azali's own actions and writings. This illustrates the intricate web of religious, political, and personal motivations that underpinned the various groups participating in or reacting to the constitutional movement. The presence of such diverse groups, with their own agendas, contributed to both the dynamism and the ultimate fragility of the revolution.Spaces of Tension and Public Expression

The constitutional revolution was not confined to parliamentary debates or royal decrees; it manifested in the daily lives of ordinary Iranians. This paper examines the spaces and ways through which social tensions during the constitutional revolution manifested, and explores how this evidence engages with Benedict Anderson’s view that religious communities and dynastic realms must fade. Public spaces like bazaars, mosques, and coffeehouses became crucial arenas for political discussion, protest, and the dissemination of ideas. Clandestine printing presses churned out revolutionary tracts, and public demonstrations became a common sight. These spaces allowed for the formation of a nascent "public sphere," where citizens could engage with political issues and collectively express their demands. The constitutional movement in Iran, therefore, was not just an elite-driven phenomenon but a popular uprising that utilized and transformed existing social spaces for political ends, challenging traditional hierarchies and fostering a sense of shared national identity.Legacy, Global Context, and Enduring Impact

Despite its failures and the subsequent periods of authoritarian rule, the constitutional movement succeeded in profoundly altering Iran’s social and political fabric. It paved the way for later reforms and modernization efforts, introducing concepts of parliamentary governance, a written constitution, and a more defined legal framework. The very idea of limited monarchy and popular sovereignty, once alien, became ingrained in the political consciousness of the nation.Global Context

It's important to recognize that the Iranian Constitutional Revolution was not an isolated event. These two revolutions (referring to the Russian Revolution of 1905 and the Young Turk Revolution) were part of a global trend of revolutionary politics that swept the globe at the turn of the 20th century. From Russia to the Ottoman Empire, nations grappled with similar challenges of modernization, imperialism, and the demand for greater political participation. Iran's constitutional movement, therefore, was a significant part of this broader wave of change, reflecting universal aspirations for self-determination and representative government.Victims and Aftermath

The path to constitutionalism was paved with significant human cost. While the immediate aftermath of the 1908 bombardment saw executions and repression, the broader struggle for political freedom in Iran continued for decades. The statistical breakdown of victims covering the period from 1963 to 1979 adds up to a figure of 3,164. Of this figure, 2,781 were killed in nationwide disturbances in 1978/79 following clashes between demonstrators and the Shah's army and security forces. While these later figures pertain to the lead-up to the 1979 Islamic Revolution, they underscore the enduring struggle for political change that began with the constitutional movement. The legacy of the constitutional movement in literature also highlights its lasting impact on Iranian thought and identity, serving as a constant reminder of the nation's aspirations for justice and self-governance. The work of scholars like Ali Akbar Mahdi, a sociology professor at California State University, Northridge, with a Ph.D. in sociology from National University Iran and an M.A. in sociology from Michigan State University, continues to shed light on the sociological dimensions of this pivotal period, emphasizing its profound and lasting influence on Iranian society. In conclusion, the constitutional movement in Iran was a watershed moment, a dramatic break from centuries of absolute monarchy. It introduced the enduring concepts of a constitution, parliament, and popular sovereignty into Iranian political discourse. While its immediate successes were often short-lived and its path fraught with violence and setbacks, its fundamental achievement lay in permanently altering the political consciousness of the Iranian people. It ignited a flame of desire for self-governance and accountability that, despite subsequent periods of authoritarianism, continued to burn, influencing every major political upheaval in Iran thereafter. What are your thoughts on the enduring legacy of the Constitutional Revolution in modern Iran? Share your perspectives in the comments below, and don't forget to explore our other articles on Iranian history and political developments!

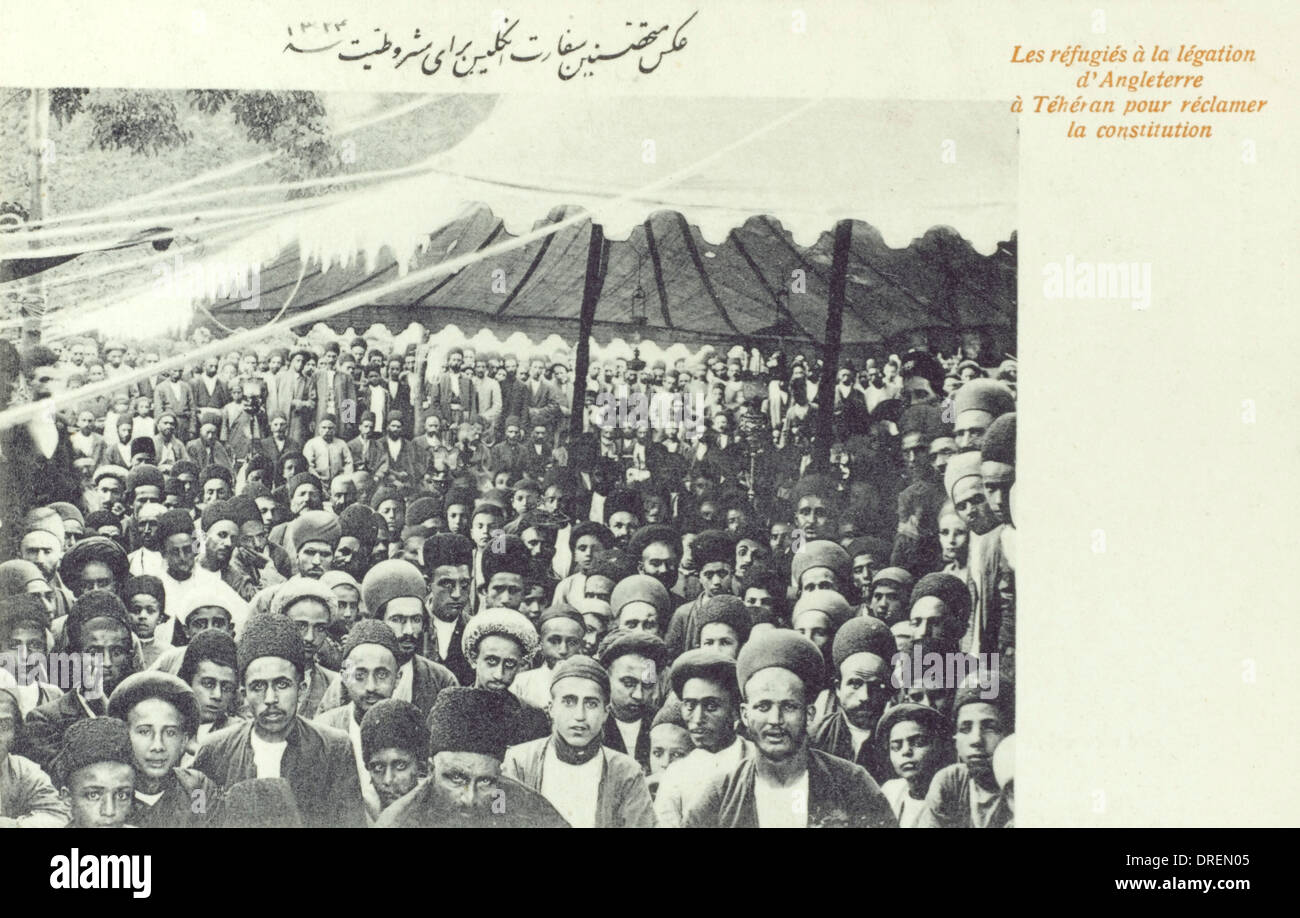

The Constitutional Revolution in Iran (4/4 Stock Photo - Alamy

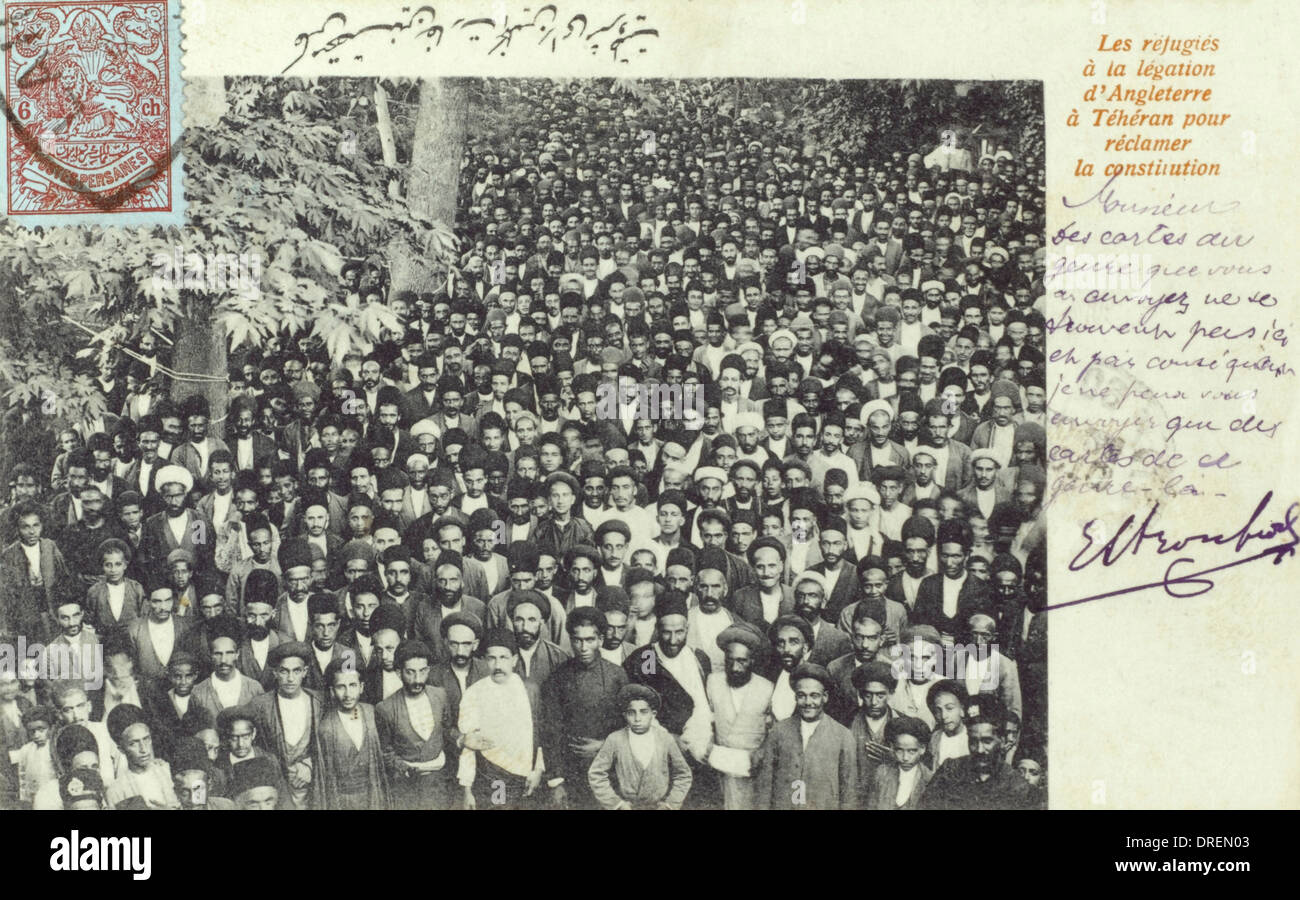

The Constitutional Revolution in Iran (3/4 Stock Photo - Alamy

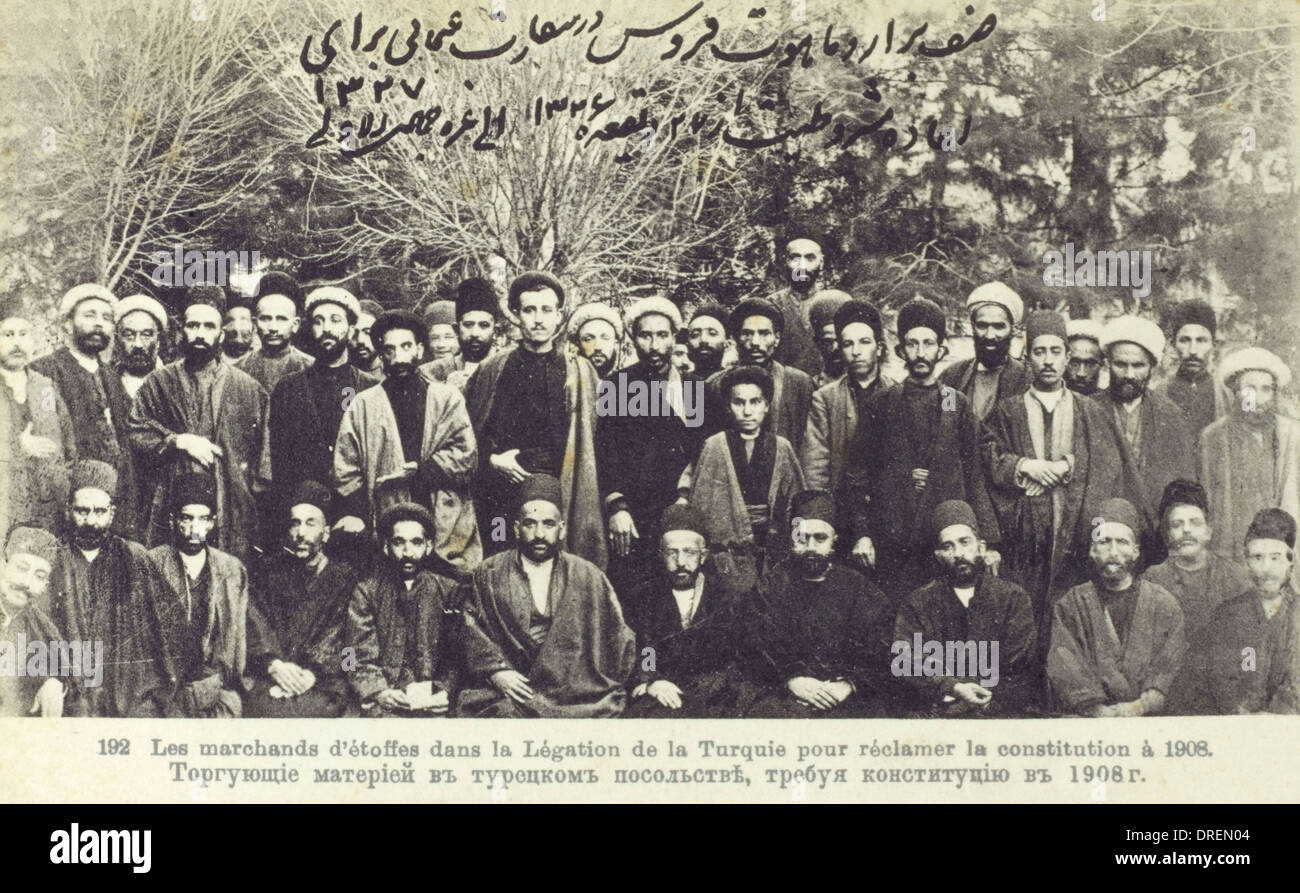

The Constitutional Revolution in Iran (2/4 Stock Photo - Alamy