Two Paths To Modernity: Contrasting Turkey And Iran's Emergence

The early 20th century marked a pivotal era for the Middle East, witnessing the dramatic collapse of old empires and the rise of new nation-states. Among the most significant transformations were those in Turkey and Iran, two neighboring countries that embarked on ambitious modernization projects in the wake of global upheaval. While both nations shared a desire to shed the vestiges of their imperial pasts and embrace a more contemporary identity, their journeys diverged significantly, shaped by unique leadership, societal structures, and geopolitical circumstances. This article will delve into the fascinating contrast between the emergence of modern Turkey and Iran, exploring their shared aspirations and their ultimately distinct paths.

The historical trajectory of these two powerful nations offers a compelling case study in state-building and national identity formation. From the ashes of defeated empires, strong leaders rose with visions of reform, aiming to redefine their countries' places in a rapidly changing world. Yet, the methods employed and the societal impacts achieved varied dramatically, leaving lasting legacies that continue to influence their respective political and social landscapes today. Understanding these foundational differences is crucial for comprehending the complexities of the contemporary Middle East.

Table of Contents

- The Ottoman Legacy and Turkey's Rebirth

- Iran's Constitutional Stirrings and Pahlavi Ascent

- Shared Aspirations: Modernization and Westernization

- Divergent Paths: Secularism and Social Reform

- Geopolitical Positioning and Regional Ambitions

- Internal Dynamics and Societal Shifts

- Bilateral Relations: Security and the Kurdish Question

- Lessons from Two Modernities

The Ottoman Legacy and Turkey's Rebirth

The story of modern Turkey is inextricably linked to the dramatic collapse of the Ottoman Empire, a vast and once-mighty dominion that had spanned centuries. Defeated in World War I, the empire was dismantled, leaving a power vacuum and a fragmented populace. It was from these remnants that modern Turkey was founded in 1923, under the resolute leadership of national hero Mustafa Kemal. Later honored with the title Atatürk, or "Father of the Turks," Kemal envisioned a completely new nation, shorn of its imperial and religious baggage, and oriented firmly towards the West.

- Air Force Iran

- Iran Rial To Usd

- Iran President Dies

- Iran President Ahmadinejad

- Is It Safe To Travel To Iran

Atatürk's program of reforms was nothing short of revolutionary. He embarked on a series of radical social, legal, and political changes designed to transform Turkey into a modern, secular republic. This involved abolishing the caliphate, replacing Islamic law with a secular civil code, adopting the Latin alphabet, and promoting Western dress and education. His approach was often described as anti-religious, aiming to relegate religion to the private sphere and remove its influence from public life and state affairs. As one source notes, "Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who managed to establish Turkey on the remains of the Ottoman Empire, tried to modernize Turkey with antireligious approach." This top-down, comprehensive overhaul was central to the emergence of modern Turkey.

The historical significance of this period is well-documented. Bernard Lewis, a renowned historian and expert in Middle Eastern and Islamic history, extensively covered this transformation in his seminal 1961 book, "The Emergence of Modern Turkey." The book traces the country's journey from the decline and collapse of the Ottoman Empire up to its contemporary period, providing a detailed account of the profound changes initiated by Atatürk. His work highlights how Kemal's modernization efforts were a primary catalyst for the social and religious shifts that defined modern Turkish society.

Two key goals shared by Turkey and Iran in the years following World War I were to modernize and to assert their independence from external powers. For Turkey, this meant a decisive break from its Ottoman past and a deliberate pivot towards European models of governance and society. The birth of this new republic, marked by the declaration in 1923, was a testament to Atatürk's unwavering commitment to creating a sovereign, secular, and modern state, fundamentally reshaping the country's identity and its place in the world.

Iran's Constitutional Stirrings and Pahlavi Ascent

While Turkey was forging its new identity from the ashes of a defeated empire, Iran, though never formally colonized, faced its own set of internal and external pressures. The Qajar dynasty, which had ruled Iran for over a century, was increasingly seen as corrupt and ineffective, struggling to maintain sovereignty against the encroaching influence of Great Britain and Russia. This period saw "constitutional revolutions in the Ottoman Empire and Iran in the early twentieth century," as Nader Sohrabi's work suggests, reflecting a global diffusion of ideas about governance and reform.

Iran's path to modernity was characterized by a different kind of upheaval. Instead of a direct imperial collapse, it was a gradual decline and a struggle against internal weakness and external interference. The desire for reform culminated in the Constitutional Revolution of 1906, which sought to limit the Shah's power and establish a parliamentary system. However, true consolidation of power and a more centralized modernization drive came later, with the rise of Reza Khan.

In 1925, Reza Khan, a military officer, successfully toppled the rotten Qajar dynasty and took hold of the throne, establishing the Pahlavi dynasty. Like Atatürk, Reza Shah, as he became known, harbored ambitions of modernizing Iran and strengthening its national sovereignty. He too sought to introduce reforms inspired by Western models, including developing infrastructure, establishing a modern army, and promoting secular education. His reign marked a significant period of state-building and an attempt to integrate Iran more fully into the global system, moving away from its more traditional, isolated past.

However, the nature and pace of Reza Shah's reforms differed from Atatürk's. While both leaders pursued westernization and secularization, the depth and radicalism of these changes varied. For instance, in terms of societal transformation, particularly in the realm of architecture, Iran's approach to modernity was often described as an "imitated modernity," manifesting as "comparative or eclectic or modern or neoclassic architecture." This suggests a more selective adoption and adaptation of Western forms rather than a complete break, reflecting a different societal and political context compared to Turkey's more sweeping changes. The emergence of modern Turkey and Iran, while sharing a common impulse for change, thus unfolded through distinct processes.

Shared Aspirations: Modernization and Westernization

Despite their distinct historical contexts and the different routes they took, the leaders of modern Turkey and Iran shared fundamental goals in the years following World War I. Both Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and Reza Shah, upon coming to power, recognized the urgent need to reform their countries. Their primary objectives included strengthening national sovereignty, modernizing their states and societies, and integrating more effectively into the global system. As noted, "what were two goals shared by Turkey and Iran in the years following World War 1" were precisely these aims of modernization and national consolidation.

Both leaders were acutely aware that their nations, previously defined by their imperial legacies, needed to adapt to a new world order dominated by Western powers. This recognition led them to pursue policies of westernization and secularization. They understood that adopting Western administrative, legal, and educational systems, as well as promoting Western-style social norms, was perceived as essential for progress and for asserting their countries' independence. They sought to "separate them from western countries as well as from north africa and the middle east countries where modernization has been initiated, rather lately, through the practices of colonization." This implies a desire to modernize on their own terms, without succumbing to the direct colonial practices that had affected other parts of the region.

The drive for modernization in both countries was also a response to internal conditions. Both the Ottoman Empire and the Qajar dynasty were seen as stagnant and incapable of addressing the challenges of the 20th century. Atatürk and Reza Shah aimed to create strong, centralized states capable of defending their borders and fostering economic development. They both sought to dismantle old feudal structures and build modern institutions, from legal systems to educational frameworks, that would support a new national identity. This shared ambition for a revitalized, independent, and modern nation was a powerful unifying force in their respective early republican periods, setting the stage for the unique paths that would define the emergence of modern Turkey and Iran.

Divergent Paths: Secularism and Social Reform

While the aspirations for modernization and westernization were shared, the methods and the extent to which these reforms were implemented, particularly concerning secularism and social change, marked a significant divergence between Turkey and Iran. This is perhaps the most striking contrast in the emergence of modern Turkey and Iran.

Women's Rights: A Stark Divide

One of the most telling distinctions in their modernization efforts concerned the status of women. In Turkey, under Atatürk's radical reforms, women were granted significant new rights. This included the right to vote and hold public office, access to education, and legal equality in marriage and divorce. As explicitly stated in the provided data, "the difference between turkey and iran when they modernize is that turkey gave woman equal rights as men but in iran woman didn't have that right." This fundamental difference reflected Atatürk's deep commitment to a fully secular and egalitarian society, where gender equality was seen as a cornerstone of modernity.

In Iran, Reza Shah's reforms, while progressive in some areas, did not extend to granting women equal rights in the same comprehensive manner. While there were efforts to promote women's education and discourage the veil in public spaces, the legal framework regarding family law and political participation remained largely traditional. This disparity in women's rights highlights the differing approaches to social engineering and the varying degrees of willingness to challenge deeply entrenched societal norms in the name of modernization.

The Role of Religion and State

The approach to religion was another critical area of divergence. Atatürk's modernization in Turkey was characterized by a forceful and often "antireligious approach." He systematically dismantled the institutions of the Ottoman caliphate, closed religious schools, banned religious attire in public institutions, and replaced religious courts with secular ones. The goal was to create a strictly secular state where religion had no role in governance or public life. This radical secularism was a defining feature of the emergence of modern Turkey, aiming to remove the influence of the traditional religious elite (the ulama) from state affairs.

In Iran, Reza Shah also sought to reduce the power of the religious establishment and introduce secular elements into the legal and educational systems. However, his approach was less confrontational and less comprehensive than Atatürk's. The ulama, while their influence was curtailed, were not entirely stripped of their societal role. This difference laid the groundwork for future developments. In later periods, particularly in Iran, the "earlier division of many societies, rooted in a bifurcation of education, into a modern secular vs. more traditional religious elite (the ulama), is complemented today by a modern educated but more islamically oriented sector of society." This suggests a more complex and evolving relationship with religious identity in Iran, in contrast to Turkey's more rigid initial secularization.

Geopolitical Positioning and Regional Ambitions

The contrasting internal reforms in Turkey and Iran also profoundly influenced their respective geopolitical alignments and regional ambitions. The emergence of modern Turkey saw it firmly align with the Western bloc, particularly during the Cold War. Turkey's inclusion in NATO and its long-standing application to the European Union are clear indicators of its strategic choice to integrate with Western institutions and values. This orientation has shaped its foreign policy, its military doctrine, and its economic development for decades. Its involvement with the politics of the Middle East has often been viewed through the lens of its Western alliances, even as it seeks to project its own regional influence.

Malik Mufti's work provides a novel explanation for Turkey's geopolitical reorientation, using the notion of "little America" as an expression of Turkey's emerging bid for regional hegemony. This concept suggests Turkey's ambition to project a similar kind of influence and model in its immediate neighborhood as the United States does globally, albeit on a smaller scale. This aspiration positions Turkey as a significant actor seeking to project its power and values, often balancing its Western ties with its growing engagement in the Middle East and beyond.

Iran, on the other hand, pursued a more independent and often non-aligned foreign policy, particularly after the 1979 Islamic Revolution. While Reza Shah initially sought Western ties, Iran's post-Pahlavi trajectory saw it distance itself from Western influence, carving out a unique path in the international arena. Its geopolitical ambitions have been more focused on regional power projection within the Middle East, often through alliances with non-state actors and a more confrontational stance towards Western powers. The data mentions Iran fighting "this war rather effectively," referring to its involvement in conflicts like the Syrian civil war, demonstrating its capacity and willingness to project power and influence through various means in the region.

The differing geopolitical orientations of Turkey and Iran reflect their distinct internal ideologies and the legacies of their modernization processes. Turkey's secular, Western-oriented identity contrasts sharply with Iran's post-revolutionary Islamic identity, leading to divergent foreign policy priorities and regional roles, even as both remain significant players in the Middle East.

Internal Dynamics and Societal Shifts

Beyond the grand narratives of state-building and geopolitical positioning, the emergence of modern Turkey and Iran also involved complex internal societal shifts. The leaders in both countries sought to transform not just political structures but also the very fabric of their societies. The "similarities and differences between the two countries' societies" are crucial for understanding their distinct paths.

In Turkey, Atatürk's modernization could be regarded as one of the main factors for the social and religious changes in modern Turkey. His reforms aimed to create a homogeneous Turkish national identity, often at the expense of minority cultures and traditional religious practices. The abolition of the fez, the adoption of Western dress, and the emphasis on a secular education system were all designed to re-engineer Turkish society from the ground up, fostering a modern, secular citizenry. This created a significant divide between the urban, Westernized elite and the more traditional, rural populace, a tension that continues to play out in Turkish politics today.

In Iran, while Reza Shah also pursued social reforms, including promoting education and discouraging the veil, the impact was less pervasive and more uneven. The traditional religious elite, the ulama, maintained a stronger social base and cultural influence compared to their counterparts in Turkey. This meant that while modern, secular institutions were established, they often coexisted with, rather than completely replaced, traditional structures. This dynamic led to a different kind of societal evolution. The emergence of an "alternative islamically activist elite" reflects the new realities of the Muslim world, where a "modern educated but more islamically oriented sector of society" has emerged, challenging the earlier binary of secular vs. religious elites.

Both countries experienced a top-down imposition of modernity, but the societal response and the enduring influence of traditional institutions varied. Turkey's more radical break created a clearer, though often contested, secular identity. Iran's more gradual and less absolute secularization meant that religious identity remained a powerful force, eventually leading to a revolution that redefined its path, highlighting the different ways societies adapt to or resist imposed changes during the emergence of modern Turkey and Iran.

Bilateral Relations: Security and the Kurdish Question

The relationship between Iran and Turkey, two neighboring countries that witnessed significant historical and political developments over a nearly identical period, has been shaped by their respective internal transformations and geopolitical alignments. After the emergence of modern states, Iran and Turkey were mostly preoccupied with security issues, which dominated relations between the two countries. Both nations, having emerged from periods of instability and external interference, prioritized securing their borders and consolidating their national territories.

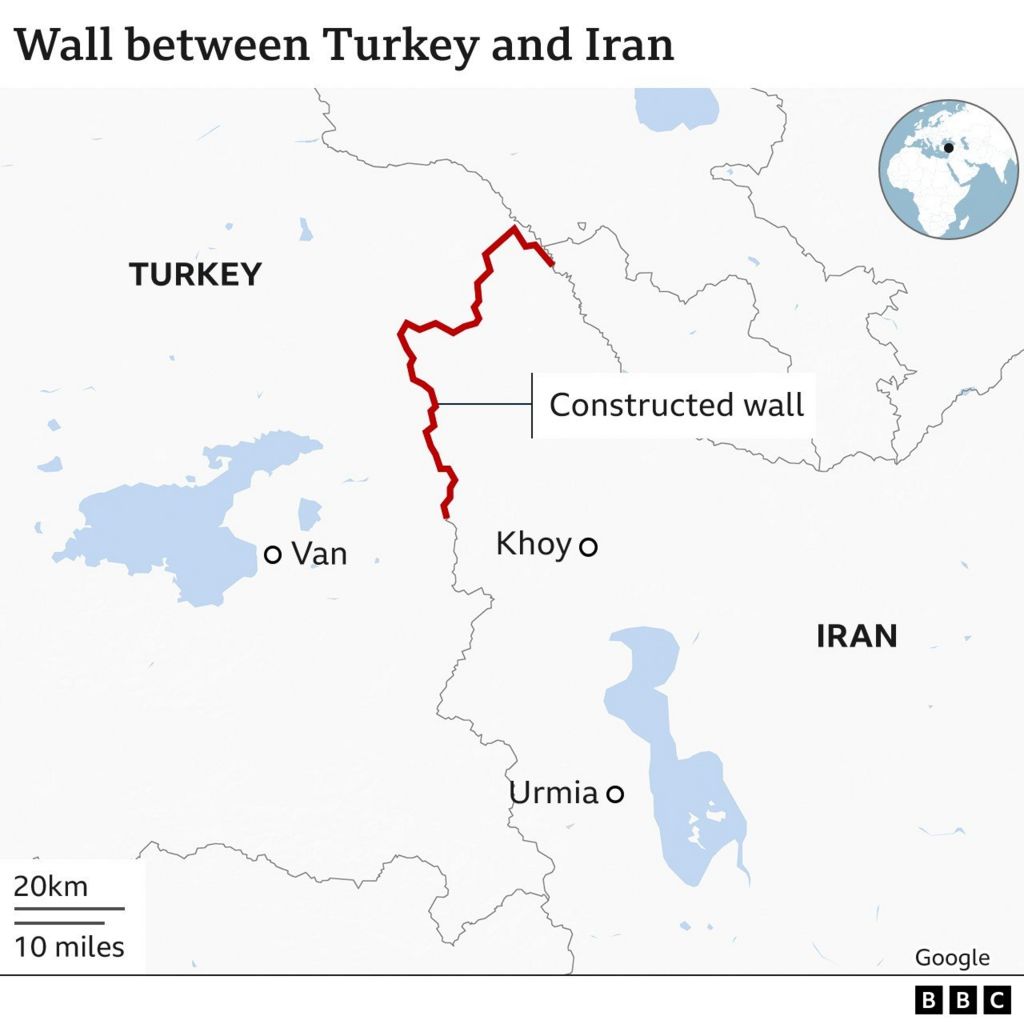

A persistent and complicated factor in the relations between Iran and Turkey has been the Kurdish question. Both countries have significant Kurdish populations within their borders, and the aspirations for Kurdish autonomy or independence have often been viewed as a security threat by both Ankara and Tehran. The cross-border movement of Kurdish groups, and the historical grievances of Kurdish communities, have frequently led to tensions and necessitated cooperation, or at least careful management, between the two states. This shared internal challenge has often overshadowed other aspects of their bilateral relationship, forcing them to engage on security matters even when their broader foreign policy orientations diverged.

Despite their differing ideologies and alliances, both Iran and Turkey have maintained a pragmatic relationship, often driven by mutual security concerns and economic interests. While Turkey's inclusion in NATO and its application to the European Union placed it firmly in the Western camp, and Iran's post-revolutionary stance often put it at odds with Western powers, the necessity of managing their shared borders and regional challenges has often compelled them to engage. The history of their modern states is thus not just a story of internal transformation but also of complex, often cautious, interaction with each other, particularly concerning issues of national security and the management of shared ethnic populations.

Lessons from Two Modernities

The contrasting emergence of modern Turkey and Iran offers invaluable lessons on the complexities of nation-building, modernization, and the enduring power of culture and religion. Both countries embarked on ambitious projects to redefine themselves in the 20th century, driven by strong leaders who sought to propel their nations into the modern era. Yet, their paths diverged significantly, leading to distinct political systems, societal structures, and international alignments.

Turkey, under Atatürk, pursued a radical, top-down secularization and Westernization, fundamentally reshaping its legal, social, and political institutions. This included granting women equal rights and largely removing religion from the public sphere. This bold experiment aimed to create a modern, European-style republic, and its legacy continues to define Turkish identity and politics, even amidst contemporary debates about its secular foundations.

Iran, under Reza Shah, also sought modernization and Westernization but adopted a more cautious and less comprehensive approach to secularization. While reforms were introduced, the religious establishment retained a stronger foothold in society, and women did not achieve the same level of legal equality as in Turkey. This more nuanced engagement with tradition and modernity ultimately contributed to a different societal evolution, one that saw the eventual re-assertion of religious authority in a revolutionary context.

The two cases highlight that while global ideas of modernity may diffuse, their "regional and local reworking and the long term consequences of adaptations" can vary dramatically, as Nader Sohrabi's work suggests. The collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the decline of the Qajar dynasty created unique windows for national transformation. However, the specific choices made by their leaders, the existing societal dynamics, and the geopolitical environment each nation found itself in, led to profoundly different outcomes. The paths taken by Turkey and Iran illustrate that there is no single blueprint for modernity, and that the interplay between leadership, tradition, and external pressures shapes the destiny of nations.

Conclusion

The emergence of modern Turkey and Iran represents two compelling, yet distinct, narratives of nation-building in the 20th century. Both countries, rising from the ashes of old imperial systems, shared a fervent desire for modernization, westernization, and national sovereignty in the aftermath of World War I. However, the radical secularism and comprehensive social reforms championed by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in Turkey starkly contrasted with the more measured, and ultimately less enduring, secularization efforts of Reza Shah in Iran. This divergence is particularly evident in the realm of women's rights and the role of religion in public life, where Turkey embraced a revolutionary break from tradition while Iran maintained a more complex, and ultimately volatile, relationship with its religious heritage.

These foundational differences have shaped not only their internal societal dynamics but also their geopolitical orientations, with Turkey aligning with the West and Iran pursuing a more independent path. The historical journeys of these two powerful neighbors offer a rich tapestry of lessons on the challenges and complexities of transforming ancient civilizations into modern states. Understanding these contrasting paths is essential for anyone seeking to grasp the intricate dynamics of the contemporary Middle East. We encourage you to delve deeper into the histories of these fascinating nations and share your thoughts in the comments below. What aspects of their modernization journeys do you find most compelling?

- Women Of Iran

- Us And Iran Conflict

- Persian Rugs From Iran

- Did Isreal Attack Iran

- Islamic Republic Of Iran Army

Afghan migrants kidnapped and tortured on Iran-Turkey border - BBC News

Afghan migrants kidnapped and tortured on Iran-Turkey border - BBC News

Turkey, Iran Spread Islamist Thought to American Students | National Review